Featured Post by Sian Wu of That’s Amasian!

It’s a common experience for most Asian Americans: people assuming that we can’t speak English. This misjudgment confronts us on the street—yelled angrily at us and muttered under people’s breath. It can be unwittingly revealed at social events by people who compliment us on “how good our English is!” It even surfaced in the midst of this year’s gubernatorial race, when a Rob McKenna staffer tweeted, “Shut up and speak English #Asians.”

Asian Americans who only speak English find this particularly ironic. For me, as a fluent English speaker who majored in English lit and is probably more familiar with Spenser, Coleridge and Dickinson than your average racist on the street, this stereotype is particularly laughable.

I didn’t start learning Mandarin until college, where I studied abroad in Shanghai, so I’ve experienced both sides of the fence: an Asian American who communicates in English only, and someone who can speak both English and the language of my family’s heritage.

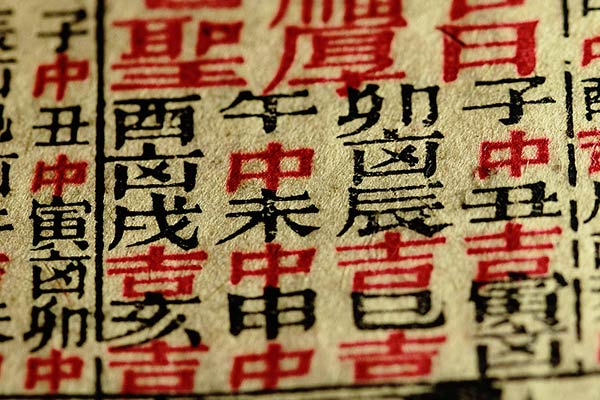

For me, I wanted to be able to communicate with my relatives and better understand where I came from. Mandarin curriculum wasn’t an option in high school, and my parents pulled us out of Chinese school when I was little—the fact that we hated it and was an hour’s drive away helped them along in that decision. So in college I dove in and double majored in Chinese, and never regretted it. The experiences and people I was able to meet through learning my heritage’s native language have helped shape who I am today.

But I can understand the perspective of other APIs, who feel that learning Vietnamese, Japanese or any of the hundreds of dialects from their home countries isn’t something that they want or need to do.

Read more at Tongue Tied: Are we losing our ethnic language?

I do want the kids to feel some connection to their ancestry, so we have a Chinese tutor to help them learn Mandarin. It would be fabulous if they were fluent some day. I’d love to see them order off the Chinese menu!

I’m not sure which is more irritating, having people assume I don’t speak English or having people assume that I do speak the randomly selected Asian language of their choice. (The latter happens far more often.)

My father’s approach to our heritage was always completely independent of speaking Mandarin; as far as he’s concerned, it’s about attitudes toward family, education, etc., a sense of history, and so on. Now that my grandparents are gone, the Chinese I speak is really only useful on the very rare occasions when I go to a Mandarin speaking restaurant without my family (around here the proprietors are mostly speakers of other dialects), and that’s just not that meaningful to me. Sure, it’d be nice to be fluent, but that’s about as far as it goes.

I went to Chinese school for most of my childhood and hated it. The curriculum was such that they put us in by age (not level) so that there kids in my class that were fluent. I felt like the dumbest kid in class. The lessons did not build on each other. They were photocopied from somewhere and were straight memorization. It wasn’t until college that I reached out to voluntarily learn Chinese on my own. Took 2 years of it and learned more than during all those years as a child because the curriculum was created to learn in a structured manner that built on the previous lessons. I so worry my child will “lose” her heritage if she doesn’t know how to speak Chinese, but I also know it’s an uphill battle since I’m not fluent and therefore cannot reinforce the language with her at home.

Thanks for commenting on my story! I think there’s a disproportionate amount of pressure to learn and be fluent in our native language because of our Asian race. No one acts super surprised when 2nd generations of Americans of French or German heritage aren’t fluent–they’re lauded for making the effort and being passable! I think part of the pressure also comes from within our own families and communities, since there is so much pride about the beauty and history of language (I especially notice it with Chinese). My kid is half Chinese half white American, and he does know a bit of Chinese but English is his dominant language. I wish I were more comfortable in Mandarin so that he’d be fluent, but the exposure he gets at Mandarin daycare is definitely valuable.

Am CBC –Canadian born Chinese (CBC is also our all-Canadian Broadcasting Channel, a long standing Canadian national tv, radio production organization that is…strongly Canadian for decades. So much for the pun…all Canadian.)

Am I less ethnic for speaking Chinese so badly now? Or in the case of my nieces and nephews unable to speak any Chinese?

I guess being “ethnic” or of Asian descent is best and most broadly in positive sense is celebrating and integrating aspects of culture into daily life and in your consciousness. It’s not just about speaking the language…but knowing and preparing food, knowing some in-slang/colloquialisms, fashion/pop trends, history of Asians in North America (not Asia, that’s way too much memory and effort for thousands of years of history!!), art, etc.

Language can help alot but it’s not the ultimate distinguisher. Attitude and intuition and capacity to interact successfully among fully assimilated, half-assimilated, or recent immigrant, etc. social groups would contribute to a person’s ethnicity.

It’s hard

because it’s hard to maintain your heritage language in a non-language speaking country

yet because of our race, we’re inextricably tied to it, so i’m not even sure if we should be able to speak it

and if we can, when we should use it

also, how often will it be used in america?

is going back and finding out you can’t speak it really that big of a deal or that bad of a feeling?

it’s all about survival of the fittest and in america, where western culture predominates, asian culture is weeded out and eliminated, voluntarily or involuntarily, to the anglo dominant culture that eventually prevails

don’t you agree?